Pocket-sized Beethoven: the CD of the 19th century

by Jan Van den Bossche

You probably have recordings of a few Beethoven symphonies somewhere at home. Indeed, many music lovers have several complete works tucked away, and may compare versions by Toscanini, Bernstein or Karajan. Furthermore, those who enjoy historically informed performances can also elect to hear recordings by particular conductors such as Norrington or Gardiner.

In Beethoven’s era, the situation could not have been more different. The performance of a symphony by a professional symphony orchestra, well prepared and put together in a balanced way, was a rarity. The chance of hearing a Beethoven symphony in a provincial town was virtually zero, and even in cultural hubs such as Vienna or Paris there were very limited opportunities.

The orchestra as an institution

Orchestras have been linked to courts or churches since time immemorial. In the 18ᵗʰ century, an increasing number noble families kept their own orchestras, but a bourgeois concert life featuring regular concert series with symphonic repertoire only took off during the 19ᵗʰ century. The majority of large orchestras still in operation today (Berlin, London, Amsterdam, Boston, etc.) were only founded in around 1900.

Beethoven’s career unfolded in an era of transition, the time of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. He was still largely dependent upon the patronage of music-loving aristocrats. However he also organised his own concerts, for which he would assemble an orchestra with great difficulty.

CD

Imagine being present at one of these concerts organised by Beethoven, at which his Sixth Symphony, the ‘Pastorale’, is being performed for the first time, and knowing that this would most likely be both the first and the last time you would ever hear this beautiful music. This is unthinkable for us. These days, we can put on a CD at home afterwards, or search for the work on Spotify. We can repeat a favourite passage ten times over, simply fast-forward to skip through a section that we find less appealing.

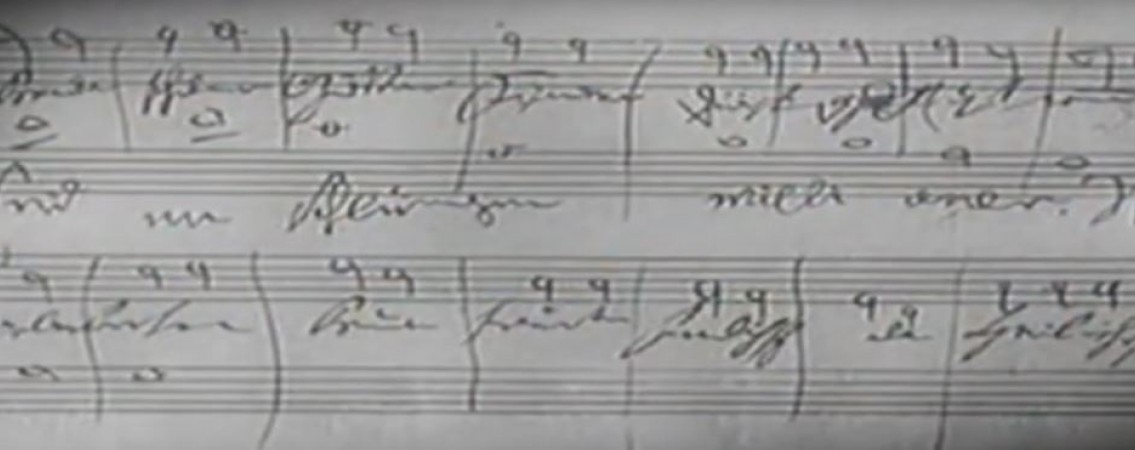

In the 19th century, the relationship with the repertoire was entirely different. When a concert audience found a work especially beautiful, they could shout ‘encore’ and it would be played again; this would happen in the middle of an opera or symphony. However once the performance was over, they were confined to arrangements for smaller line-ups, which could even be played in a domestic setting.

A culture of recycling

Beethoven lived and worked in an era in which artists were enjoying growing prestige, and in which artworks (books, paintings or pieces of music) were beginning to be regarded as something finished, ‘ready’ for perpetuity. But the overall culture at that time was still a different one: revising, adjusting and copying continued to be very much the norm. It was customary for composers themselves to recycle the same material numerous times. Bach is a well-known example of this. The score was not an end point. Pieces of music were living organisms that continued to develop beyond the first performance. An arrangement was not automatically inferior; it was a translation and often also a tribute.

The question of authorship

The culture of arrangements gives rise to new questions with regard to authorship. Who is the ‘composer’ of an arrangement? May an arranger make adjustments and intervene in the musical discourse? In Beethoven’s time, copyright was barely regulated, and internationally it was not regulated at all. This only happened tentatively in 1886 with the Berne Convention, which at the time was signed by just eight states, including Belgium. Today there are 187 signatories.

Sometimes the arranger was the composer themself, as was the case with the version of his Second Symphony for piano trio created by Beethoven—although it is widely believed that his pupil, secretary and friend Ferdinand Ries actually performed the lion’s share of the work. The fact that the arrangement was sold as pure Beethoven was probably a marketing ploy: there was a lucrative revenue model behind the making and dissemination of chamber music arrangements of symphonic repertoire.

Piano as house orchestra

There was also such a thing as the ‘authorised’ arrangement; often commissioned by, or in any case approved by the composer. Another category was arrangements by eminent composers. One good example is Franz Liszt, who arranged all of Beethoven’s symphonies for piano. Another is Richard Wagner, who made an arrangement of the Ninth for piano. In this case, the arrangements are also a tribute.

The majority of arrangements were however aimed at the fast-growing market for sheet music for use in the domestic sphere. In the second half of the 19th century, piano arrangements flourished. The piano was the house orchestra of the bourgeoisie and the market was flooded with arrangements of symphonic repertoire for two, four and even eight hands.

Pop

Today, arranging music and reworking artworks is sometimes a controversial affair. Purists often turn up their noses at it. There is a rather more relaxed attitude when it comes to pop music, where covers or remixes are in vogue. Reworkings are also customary in film: a play, a novel or an earlier film often forms the basis for a later script. Artistic concepts can take on many forms.

Flanders Festival Ghent’s project Pocket-sized Beethoven is both a creative intervention in the coronavirus era and a tribute to an historical practice but, above all, it sheds fresh light on nine famous masterpieces.